THE DEVIL IS IN THE DETAILS

Text and research: Bastien Eblé | a new Da Vinci painting

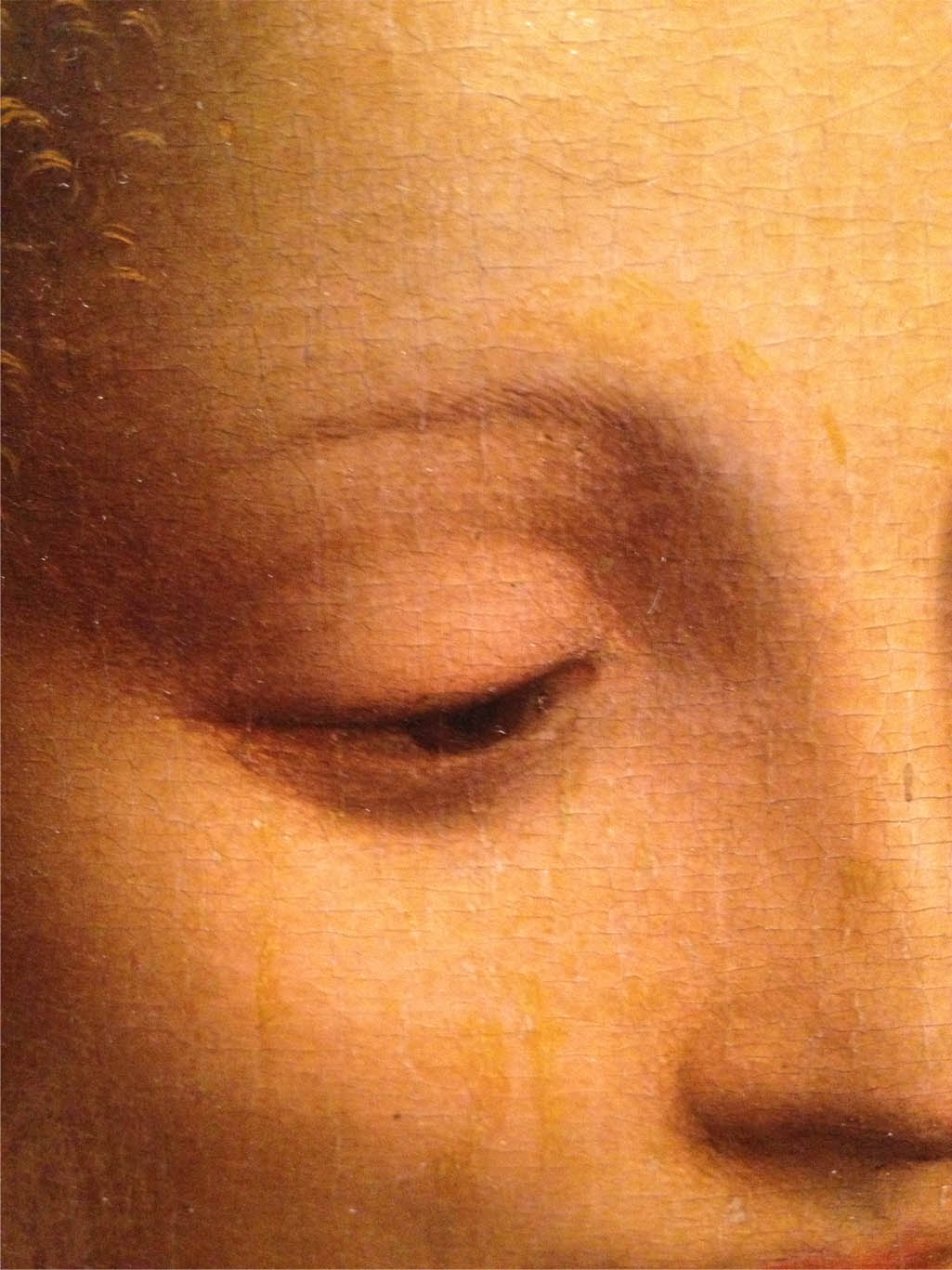

Right eye detail

Latest news on Leonardo Da Vinci: a new Da Vinci painting has been discovered.

10 Reasons to give Flora back to Da Vinci and call her Colombina again.

Part of the wonderful exhibition ‘The King and his Art’, in Dordrecht, Netherlands, is – or rather was, for the painting returned to St. Petersburg again – a painting called Flora. A flower goddess that is supposed to be painted by Francesco Melzi, the last partner and heir of Leonardo da Vinci. The woman in the picture was also called (La) Colombina. We will call her Colombina. And we argue it is and has been a Da Vinci all along. But first we look at Melzi.

Francesco Melzi accompanied Leonardo da Vinci when he moved house from Milan to Amboise in France, where they staid from 1516 to 1519. These last years of his life Da Vinci spend his time in the close vicinity of the French king Francois I.

Francesco Melzi was from an upper class family and quite talented. Leonardo was more than fond of him, but his young companion could not paint as well as the master himself. Melzi, on the other hand, was solely responsible for preserving the legacy of Da Vinci. All the works and drawings Leonardo had collected in France, Melzi returned to his parental villa in Italy, where he made a catalogue of his work and preserved everything in his possession and, for instance, gathered all of the folia into Codex’s, now world renown. Without Melzi Da Vinci would never have acquired the rock star status that he enjoys now. So, after Leonardo died, Colombina, we hold, was shipped back to Italy, together with John the Baptist and Mona Lisa. Three wooden panels of approximately the same size.

For the Dutch King William II, who was an avid art collector, this work was very attractive because it used to be a genuine Da Vinci for 350 years. He bought it and it became his prize possession. William however came into dire straits and had to sell his art collection. The Russian Hermitage museum bought most of the top pieces. Amongst them was Colombina. Probably for the first time, this year, 2014, Colombina has travelled back to Holland for the occasion of this sensational exhibition. When it was in the care of the Russians, the scholars decided in 1899 that Colombina was not a Da Vinci, but a painting by his pupil Melzi. The reasons were never clear. We argue that that was an unfair and incorrect decision. Sometimes people fail to see what is there or, in this case, what is not there.

Here are ten reasons to embrace the young lady as a real creation of Leonardo.

1. First of all, the painting is real and comes from the circle around Da Vinci (and Melzi). There’s no doubt about the question whether it was painted in the period around 1500 to 1520. Therefore it cannot be a fake. It has been known for centuries.

The circle around Da Vinci consisted of six or seven young painters. Some colleagues like Giovanni Boltrafio or Angelo De Predis. Some were younger colleagues like Solario, Marco d’Oggiono, Cesare da Sesto or Giovanni Rizzoli (Giampietrino). His first pupil and assistant Giacomo Caprotti da Oreno, nicknamed: Salai, meaning ‘little devil’ by the way, is sometimes suggested as the maker of some Da Vinci like paintings, but we don’t believe Salai could reach any significant level in painting. If this painting, Colombina, is a fruit of collegial cooperation, then other, better, painters must be suggested. Not Melzi or Salai.

2. When you take in the picture at close range you’ll see that it is of incredible beauty. It is a step up to the Mona Lisa. The knees turned to the left, the body ‘en face’ and the face turned to the right. The reason for Da Vinci to project her body, as it were, ‘straight into the camera’, is probably because the naked breast of the young woman would not work well, aesthetically, when the body was turned, as in the Mona Lisa. Da Vinci, as we shall see, also needed these outlines the achieve a second layer of meaning in the picture.

We say: a step up to the Mona Lisa, for we consider it likely that this work has been made before the Mona Lisa or during the time Da Vinci was working on the Mona Lisa. The association with Melzi comes from the Pomona picture. We will explain this later on.

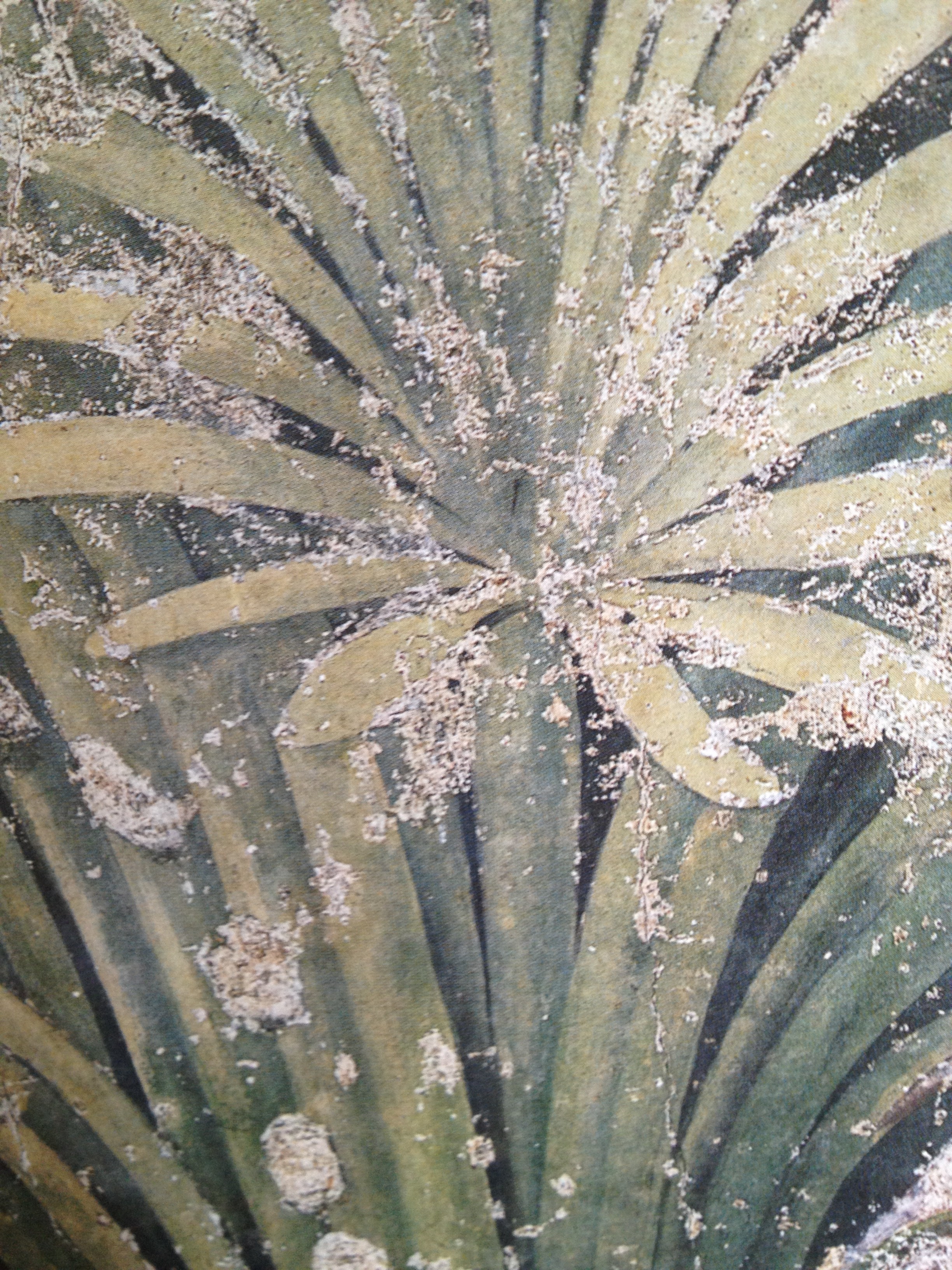

3. The first typical Leonardo detail is the set of muddy little flowers and leaves in the left corner at the bottom. Painted in a very delicate way, very dark, but still vibrant. One can admire these little plants in several works by Leonardo, for instance the, what we call, ‘Madonna on the Rocks’ as seen in Paris and in London and also in ‘Anna and Mary with the lamb’ in the Louvre in Paris.

In the first version of the Madonna of the rocks the flowers are less detailed, much like the Colombina leaves on the forground. We also looked at the leaves used in the Sforza illustration, above the Last Supper in Milan. Maybe these little four leaf clovers are not very exquisite, but the stone fern and wall snapdragon (!) in the upper corners are. In one word: beautiful. There is a six leaf flower sketched by Da Vinci in a similar way. May with this little flower Leonardo referred to his two earlier Madonna’s. The Madonna Litta and the Benois Madonna. In this last work the young woman is presenting a flower on a little stem, just like the woman in the Columbine picture does. The flower that is presented is a four leaf clover, with a purple shining, just like the flowers in the bottom left corner.

4. Colombina’s blouse shows a dazzling embroidery. It is a complex motif, consequently repeated even when the texture curves and folds. It seems to be a voile on top of a yellow satin garment. It shows a superior expression of material, worthy of Da Vinci. This kind of embroidery is typical for Da Vinci and it shows up in almost every painting from his hand. Even more close reading will lead you to the conclusion that the pattern is in fact a little devil. So here we have the following picture: the most beautiful girl in the world sprinkled with a hundred little devils. Leonardo was, as we know, renowned for his sense of humour. Or maybe Leonardo did wrestle with his devils and demons after all. We used the little devil for our website logo.

The idea of using of a voile on top of some satin garment, sprinkled with a motif with a meaning, is clearly taken from Botticelli’s Minerva. There you can see the young lady in a white gown with exquisite embroidery in the shape of the symbol of the Medici. These are the little Olympic rings. Mostly three, intertwined, some are made up out of four rings. So that’s the idea. Da Vinci himself used this motif for the first time on the sleeve of the angel figure in the second Madonna of the rocks. In fact it’s quite the same. Here Leonardo uses a typical flower motif. In the Colombina girl he changes it to a stylised little devil. Some say: I don’t see a devil or a demon in it. We do. It’s a well-known fact that Da Vinci was influenced by Botticelli, an older competitor in his hometown Florence. Daniel Arras explains eloquently how Da Vinci took the ground-breaking ideas from Botticelli’s Adoration of the Magi and incorporated these ideas in his even more ground-breaking version of the Adoration. There was also sort of rivalry between Leonardo and Botticelli going on. Botticelli once wrote that the background of a painting is not that important. ‘One can take a sponge and tap it on the painting and you’ll have a background’, was his motto. Leonardo couldn’t stand that and wrote: ‘the man is not a good painter, because he is sloppy with his backgrounds’. So one thing is certain. Da Vinci closely examined the works of Botticelli; by then already famous paintings, painted in their town, Florence.

5. The master has tied a knot into the left sleeve of her blouse. A sort of flower power solution. The other sleeve has no knot in it. One must realise that the word ‘knot’ means ‘vinci’ in the Italian language. It is a word joke Leonardo often practised in his work. A sort of a trademark.

Even the blue gown has one huge knot in it.

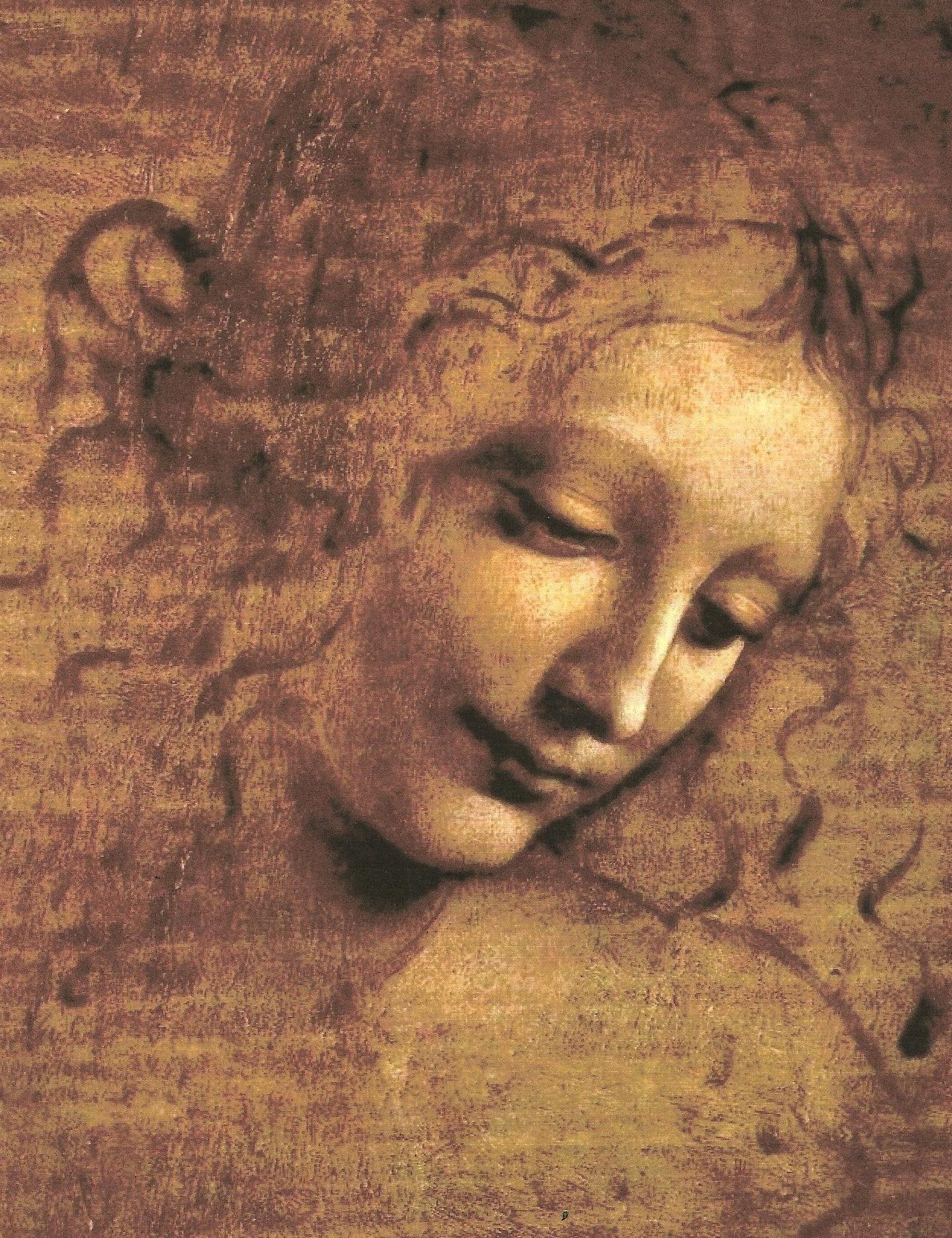

6. The young woman in the picture is a well-known Da Vinci model or shall we say the type of girl he liked.

Her face shows up in several works by Leonardo. She appears as Anna and in the Leda and the Swan studies. In that same drawing one can see the playful construction of the pigtails rounded up in a knot. The same principle is used for the coiffure of Colombina.

The closest resemblance is with a little portrait of a young woman called La Scapigliata. A wooden panel with monochrome paint. Probably a free work, not commissioned.

The Colombina girl smiles like she is in heaven, for all good reason, but we’ll get to that later on. All that hair strung on the back of her pretty head accounts for her ear being a bit flappy. A realistic rendering, not a mistake.

Some say the girl in the picture is not a portrait figure; more like an idolised beauty symbol. We disagree, and point out that the early Modonna’s that Da Vinci painted had little girlish mouths and lips, just like Colombina. She could very well be of flesh and blood.

7. The piece of jewellery that is perched between her breasts is a square ruby, with eight pearls around it, four of which are blue, all set in a golden frame, with little leafs of gold, unfolding ferns, much like euro coin symbols. Da Vinci loved depicting ladies with jewels. And this one is exquisitely rendered, letting the fabric of the blouse shine through the red crystal stone.

We included an enlargement where you can almost see an eye behind it. We’ll leave that one to the opinion of the viewers, but it would be in line with the devil motif.

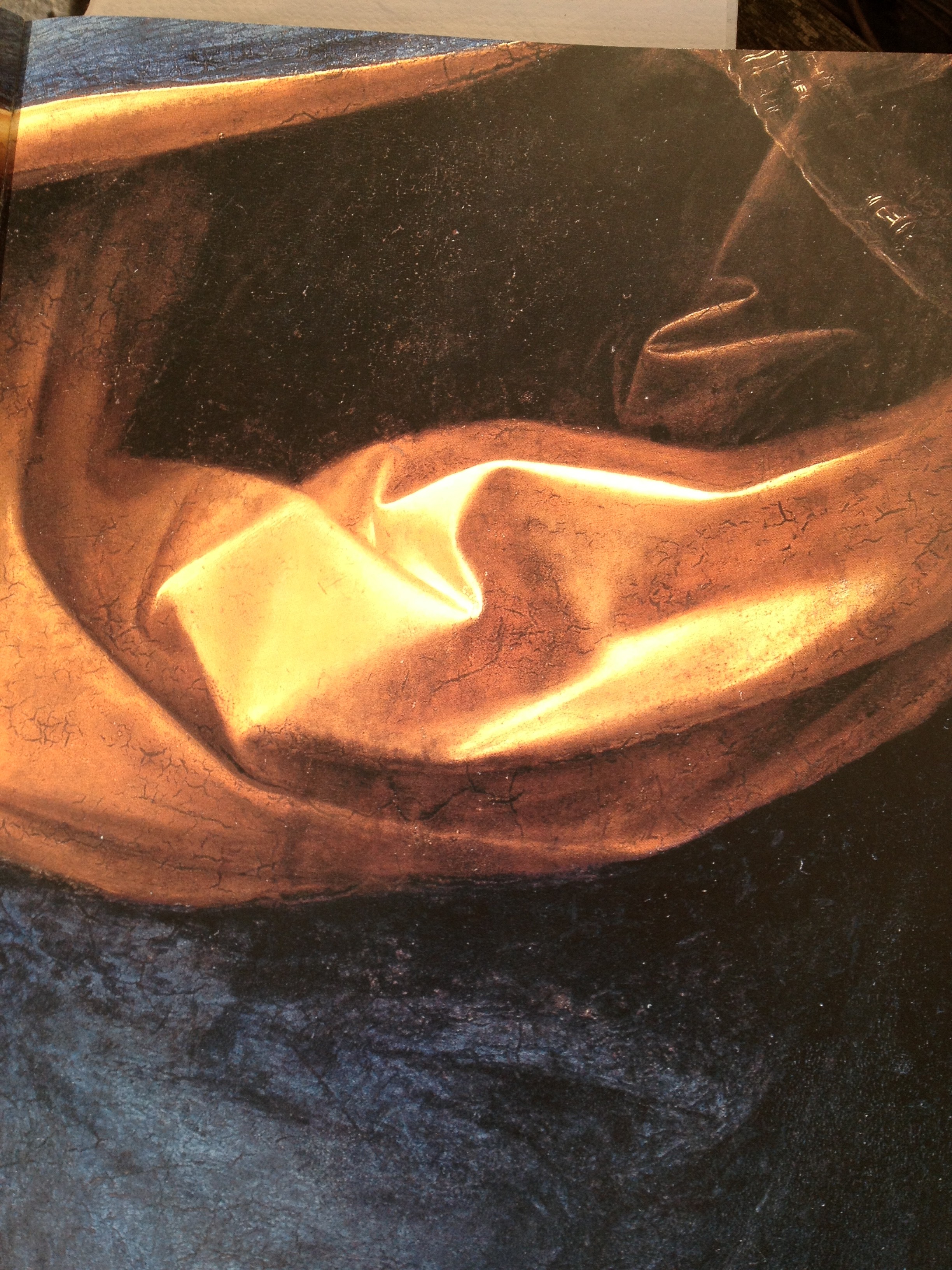

8. The blue denim fabric of Colombina’s skirt is almost identical to the fabric that clothed Anna (and Mary) with the lamb, in the Louvre. Here one sees, again, a seldom displayed expression of texture. It also reminds us of the blue skirt of the Madonna of the rocks, second version. Melzi did not reach that level. Only three signed works of his hand exist.

9. The lying hand of Colombina is almost identical to the hand of John the Baptist. She does not make the finger gesture, but she’s not far from it. The famous finger gesture of which we still not know whether it is a finger in the face of the church or directed to heaven, indicating the divine spirit. Colombina’s hand is a female variation of the male hand of John the Baptist. Her other hand could shake the hand of Mona Lisa.

Notice the lovely sfumato. Some say this kind of sfumato is not exclusive for Leonardo. That can be true, but Melzi never used it because he couldn’t.

10. Why does a decently dressed young lady show one of her breasts in public? One must realise that it is the year 1500 and this is serene setting. For ages young woman show their breast to feed their babies. This is a satisfying occupation, not only for the child, but also for the mother. And that is exactly how she’s looking towards her baby. But where is it? Well, the child that she holds is in the eye of the beholder. The baby comes into life in the imagination of the viewer, by the position of the hands, the feeding breast and the admiring looks of the mother. To suggest the presence of a child that is not depicted is a Leonardesc magic trick. Something Leonardo enjoyed greatly. Forget about the little plant, we would advise, that, by the way, is shaped like a little lantern with seven little lights shining on the (virtual) baby.

So there we have it, or better, here we have her: a young woman, a Madonna, in fact, feeding her virtual baby. Mona Lisa finally has a sister: Columbina.

On the basis of above-mentioned arguments we believe that the meaning and the theme of the painting need to be adjusted. Da Vinci didn’t set out to paint a flower goddess. The columbine is just a decoy. Da Vinci wanted to capture and combine female beauty and sexual attraction, together with motherhood and protection. Those who are saying that the painting is contrived do not understand the Da Vinci has tried to make a circle around the child. A circle of protection and a circle symbolising womb. To top it off, da Vinci did position a columbine flower above the head of the virtual child. But, unlike Melzi who also painted columbines in the lower part of his alleged version of Leda and the swan restricting himself to the purple flowers, Da Vinci took the trouble of painting the two other stages of the flower too. This is the tiny shoe shaped element closest to her cheek. The little devils do not have to be interpreted as demonic. They are meant tongue in cheek, stating that there can be a downside to all this beauty and sexual attraction.

One little devil miraculously changes into a cow, symbolising mother’s milk. On the Internet we found an interesting blog by Van Ool titled Madonna or whore (Madonna of hoer) in which he concludes that the woman in the middle is smiling as if she is looking at her baby. The writer is a trained botanist and has a university degree in art history.

Of course we asked scholars in our vicinity to comment on this analysis of the Colombina picture. Somebody said that it was important to indicate another work by Leonardo where he suggests a baby that is not there or is hidden. We wanted to keep that topic for our forthcoming book, but decided to bring a new analysis of the Madonna of the rocks 1 and 2, in this story about Colombina, in order to prove that Da Vinci went as far to suggest a baby, in this case, a child in another form. That can have implications on how the Madonna on the rocks must be interpreted. But first we look at the existing contract, in Latin, including the list of mandatory elements that the painting should contain. A whole list of details and properties. We abbreviate this list of properties.

First we want to see that the whole picture is completely done with fine gold against a prize of three lire etc…

The same goes for the Madonna’s cloak. It has to be done in gold and ultramarine.

For our Madonna’s skirt: red oil paint and another skirt gold and green.

For the setups in vermillion.

For God the father gold and ultramarine.

For the Angels above gold and clothed in Greek style.

For the mountains, sand and stones: they must be painted in oil paint of different colours.

For the side panels: four different Angels; each will play an instrument.

Therefore in all parts where our virgin appears, different colours must be used and clothing in Greek style.

Everybody must be perfect. Like the buildings and mountains and plains; everything must be executed in oil paint.

In the same way the sybils in the background must be painted.

In the same way the frame and the capitols and cutting work must be gilded.

And in the middle, the Madonna and her son as well as the Angels must be painted in perfectly fine colours.

The frame has to be painted as all inner parts.

All faces, hands and legs that are nude must be perfectly covered in oil paint.

And the place where the child sits must be painted in gold, in the form of a cross flower.

Frank Zollner places a (?) question mark behind the last demand. Other scholars conclude that the golden baby never made it to the painting. We argue that it’s there, right in the middle, where Mary’s womb or belly is projected. It’s a reclining figure, a stylised child executed in gold. A goldsmith could mould the child in 3-D. It is almost tangible. Leonardo must have gotten this idea ever since he painted the annunciation. In that painting Mary has the same golden bulge, or scarf, suggesting her pregnancy. So when Leonardo was ordered to paint the ‘Golden Child in the Middle’ he must have thought: ‘I will give you your baby in the middle’, although he hated to be ordered what to do and how to paint. The relationship between the Friars that commissioned the work and the three painters who took up the job was tense from the beginning. Eventually there was a dispute about the efforts and thus the money that this painting demanded, so they sold it to an outsider when Leonardo’s demands were not met.

A twenty year lawsuit followed, even the King of France intervened, and eventually a settlement was reached. Da Vinci and his men would paint a second version. By then Da Vinci was downright hostile to the Friars. So he must have thought, ’if I got away with the Golden Baby in disguise in the first version, I will create an even more ‘in your face’ version this second time’. There’s a lot of debate going on about the changes that were made, especially about who is looking at who; changes, compared to the first version. We conclude that in the second version all the people in the painting are now looking at the Golden Child.

For now it suffices to say that Leonardo did suggest the presence of a child, even though he is not presenting it with little toes and curly hair. The child is there however, because he was ordered to paint it that way. And yes, maybe the persons in the picture become ambivalent now. If there is a Golden Child in the middle; projected in the womb of the woman, then who is she? Or if that is Maria with the child, who are these children left and right of her? Infant bodies with mature heads? Some may find it shocking to see or suggest a golden child in the belly of Maria in a madonna painting commissioned by the congregation of the immaculate conception.

Some remarks on the attribution of works to Melzi.

Little is known about the reasons for some scholars to attribute this work to Melzi. Professor Goukowsky, connected with the hermitage museum in St. Petersburg, wanted to attribute the painting to Leonardo. Some say that in the picture the ear of the young woman is poorly proportioned or positioned. It has red tones that make it unnatural. Flappy ears, one might say. We disagree. This is really a matter of taste. So we looked at all the women’s ears Da Vinci ever painted and we came to the conclusion that there was only one. Da Vinci obviously avoided painting women’s ears. The only ear we have found was the ear of the Benois Madonna, arguably his first self-executed painting. Well then, the outcome of this enquiry is that the ear of the Benois Madonna is rather flappy, not superbly positioned and reddish. Does that make the painting any less an (early) Da Vinci? We say: all the more.

On the Internet one can easily find all kinds of discussions about the rock strata painted in the first and second Madonna on the Rocks as can be seen in Paris and in London. Some scholars argue that the second version has boulders instead of rock strata in the foreground. That would not be a logic thing to do for Leonardo, so they cast their doubts on the originality of the second version. We don’t find that a convincing argument, but these rocks strata fans will be pleased to hear and see that in the case of Colombina the painter has chosen for brown black earthly soil as a background, quite suitable for a symbol of fertility.

In previous years it has become a fashion to attribute every Da Vinci-like piece that could not be labelled ‘Da Vinci’ to Francesco Melzi. That practice has stopped, but Kenneth Clark and Carlow Pedretti, with all due respect, came up with the general idea that Melzi made copies of all the works that were sold during his lifetime. Like safety copies or so-called replacement drawings. It isn’t likely that Melzi copied this painting of Colombina. Why create a duplicate if you have the original standing next to the Mona Lisa? This is of course assuming, that the painting was made by Leonardo. Or, better, if this is the replacement copy, then where is the original? And, to top that one off: How much more Da Vinci do you want?

Melzi however did make a copy of some kind, by integrating this original work by Leonardo in his painting Pamona and Vertumnus. This painting does have a Latin mythological theme from Ovid’s Metamorphosis and surely we can see the same young woman playing a role in that picture.

But there are great differences between the original, meaning the one we think is by Da Vinci, and the variation painted by Melzi. First of all the young woman in that picture is now definitely more naked, in a see-through blouse, caught up in an erotic scene, as she is being courted by a man dressed up like an old woman. That is the story by Ovid. Melzi didn’t bother to give Pamona a piece of jewellery and the young woman’s hands do not have that symbolic gesture, which we have seen in, what we call, the original Colombina. It is therefore logical to conclude that the first wooden panel by Da Vinci was the starting point for Melzi to create his own variation.

As we dived deeper into the curious matter of the attribution of this work to Melzi we expected to encounter solid evidence and sound theories, but we haven’t found one.

My initial point of view here is: ‘if it walks like a duck and it quacks like a duck, it is probably a duck’, unless concrete evidence points out otherwise. In this case we have a stunningly beautiful painting with two or three layers of meaning, impeccably executed and reminding us in everything of Leonardo da Vinci’s painting skills. In order to refute this offspring one would expect an analysis leading to the logical conclusion that this cannot be a Da Vinci because, for instance, carbon dating points out it was painted in 1700, or samples of the paint and underground layers show that it is carrying paint Da Vinci never used, but no such thing has ever been concluded.

Instead, the discussion seems to revolve around Melzi, the alleged painter and not about Da Vinci as the maker of this work.

For a lawyer like me, this discussion is rather absurd. It goes like this:

‘I think this is a painting by Da Vinci. It has the look and feel and it is very beautiful. It comes straight out of his own studio’.

‘Well that remains to be seen, it could be painted by one of his pupils’.

‘Of course, that is possible, but not likely because it is so well painted’.

‘Still there is a possibility’.

‘Then who would you think would be able to paint such a painting?’’

‘I suggest Francesco Melzi’.

‘Why Melzi? He is not a famous painter at all. He is mentioned in two letters. One person writes: ‘I have heard(!) that he is a painter and quite a good one’. The other person writes that he was ‘a good miniaturist’. That is all that was ever said about the painting skills of Melzi. Hardly enough to suspect he had developed Da Vinci like talents’.

‘That’s very unfair. He must have learned it from the master himself. Although Vasari does not mention him, that doesn’t mean he wasn’t a good painter’.

‘Do we have any works that show that he was such a good painter?’

‘We have a pen drawing. A very famous one. A profile of Leonardo Da Vinci’.

‘Okay, that drawing is well executed, but not a sign of genius. It’s interesting because it is one of the few existing images of Leonardo’s face’.

‘He made another painting’.

‘Which one?’

‘Pomona and Vertumnus. Da Vinci (!) made a little sketch for it’.

‘Okay, so Melzi worked out a sketch and made a painting. I can follow that one’.

‘But in that painting there is a woman’s figure that looks very much like the woman in the picture called la Colombina’.

‘So?’

‘Well, don’t you see? Can’t you put two and two together?’

‘Go on’.

‘That means that Melzi must have painted both paintings’.

‘I can’t follow you there. If Da Vinci made his portrait of a young woman, with all the Da Vinci like properties in it. Then Melzi could have seen it and incorporated the young woman in a bigger picture. An idea that was sketched by Da Vinci before he died’.

In the literature this question has not been answered. Instead, the Melzians, skip this problem, and focus on the earlier criticism that Melzi was not a famous painter.

That discussion goes like this:

‘Da Vinci was a better painter than Melzi. So it’s likely that Leonardo painted this painting, because it is so well done’.

‘Melzi could have done this painting too. Look at the flowers. They are very finely painted. That is in accordance to the letter saying that Melzi was a miniaturist’.

‘Okay, let’s suppose that he could have done the flowers too, but does that mean that Da Vinci could not have painted these flowers? Or are you saying, that Da Vinci could not have painted these flowers and that therefore the whole work must be attributed to Melzi?’

‘No, that is not what I’m saying. I’m saying Melzi could have done the flowers because he was a miniaturist’.

‘So both Melzi and Da Vinci could have painted the flowers?’

‘Yes that’s correct’.

‘That leads us to where we were at the beginning’.

‘Meaning?’

‘That Leonardo could have made the flowers and the rest of this painting because he had the skills and the ideas and it looks like a genuine Da Vinci. The fact that Melzi used the woman’s figure for his own painting later on, does not mean Da Vinci could not have painted the woman. Especially because we don’t know what a typical Melzi is, since we have never seen a typical Melzi, apart from the Pomona picture, and that picture does not come close to the depth and beauty of the young woman called La Colombina.’

Even in 1919 some scholar, wrote, speaking of the Pomona picture, that Da Vinci ‘never could have painted the Lombardian vine leaves’ which are depicted in the middle. Only Melzi, who came from Lombardy, could have painted these vine leaves, and therefore she concluded, that Melzi also painted the woman called La Colombina. However, there are no vine leaves and no Lombardian landscapes or influences in La Colombina.

Until we receive better evidence to the contrary, we stick to our idea

that the beautiful young woman is painted by Leonardo da Vinci.

2014 Copyright B.F. Eblé, all rights reserved.

Bastien Eblé is a copyright lawyer in Haarlem, the Netherlands.Investors are invited to contact our site or the writer in order to investigate (and invest in) another unattributed work of Da Vincian quality.